Filming ‘Real’ Sculpture

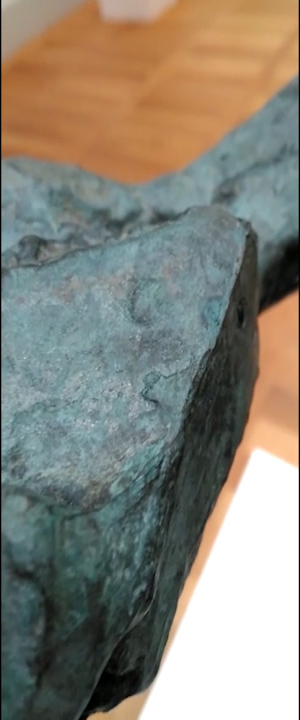

Stills from videos made by participants at 'Please Do Not Touch' workshop Tate Britain, 2016

Cameras have also been used in workshops to enable different ways of looking and of acting towards sculptures. One such workshop at Tate Britain entitled ‘Please do not touch’ (I was invited to run this workshop as part of the Tate London Schools and Teachers programme in May 2016. Referred to as a SEND Study Day, the workshop was for teachers and other arts professionals and asked them to consider ways in which young people with SEND might best use and inhabit the gallery and access the collection, through a series of practical activities) was particularly revealing. Participants were given cameras and asked to film sculptures in the collection on full zoom, trying to find ways in which the camera could offer different perspectives and ways of interacting with their physical, spatial and tactile qualities. This was predicated on two main ideas, firstly the propensity for people in galleries to step back when taking pictures, in order to get the whole thing in. A mode of viewing which emphasises pictorial composition. Secondly was the Tate’s priority for diverse groups to be able to use the galleries as they saw fit, working against traditional expectations of quiet contemplation. We were particularly interested in how young people with learning difficulties could access the collection. The irony was that touching the work was forbidden, yet to my mind, this would in many cases have been the most worthwhile and meaningful way for many of the young people I work with to access the work. Sculpture is after all tactile, spatial and massive (possessing of mass rather than being huge), and I felt should be physically experienced.

The idea to film sculptures using cameras on full zoom came initially from a reading of Alva Noë’s concept of human perception as an interconnected system of sensory experience (Noë 2004) – as opposed to what might be seen as the traditional privileging of sight as the dominant sense. Citing experiments where blind participants are able to respond to visual data received through tactile sensation, Noë shows that visual perception does not reach us purely through our eyes. In one such experiment fMRI brain imaging is used to show that tactile data is being processed within parts of the brain normally accosted with visual perception. Using technology that translates visual data from a camera into tactile sensations reproduced on the tongue, the subject (in this case one who is blind) is able to interpret visual sensations and, remarkably, recoil when a ball is thrown at the camera.

When looking closely at something, it is common to run one’s fingers over its surface in order to better make out fine detail through tactile exploration....What Finnish designer and master craftsman Tapio Wirkkala described as ‘“eyes at the fingertips”, referring to the subtlety and precision of the tactile sense of the hand.’ (cited in Pallasmaa 2009, p.54) This, I suggested to the participants, was something that might also be achieved through magnification. The question was, if we use zoom to focus in on fine surface detail, will this offer us impressions, ordinarily accessed through touch, which are forbidden in the context of the gallery?

Here, in something of a reversal of much of the studio work I had undertaken, in which the camera had encouraged the touching and handling of objects, participants created videos which attempted to gain this up-close sense of tactility through extreme close-up.

Before we began we had watched several short videos on the Tate Britain website in which works of art in the collection are discussed and filmed in a detached, measured and reflective way. (These films are available on the Tate website https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-britain/display/walk-through- british-art/1930 (Accessed: 5 September 2019)) The films made by the participants by contrast were frantic and full of movement as they used the camera to roam over the surfaces of sculptures, moving in and around, viewing them from angles which would be impossible or unlikely to be experienced by the standard gallery viewer. Unlike the videos on the Tate website, where sculptures were pictured as a whole, before certain elements were picked out and focused in on, (a structure of long view followed by close up which is typical of the way art objects are pictured in television documentaries- techniques pioneered in such programmes as John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) and Kenneth Clarke’s Civilisations (1969).), the videos created in the workshop had few if any wide shots. This meant that the impressions of texture and formal detail were not integrated clearly into the whole work as compositional elements, but were experienced as running into one another, giving these aspects an altered significance, one based in embodied experience rather than intellectual contemplation. Merleau-Ponty describes a similar sensation when gazing at the Lascaux cave paintings which follow the lines and contours of the rocky surface of the cave. ‘I would be hard pressed to say where the painting is that I am looking at. For I do not look at it as one looks at a thing, fixing it in its place. My gaze wanders within it [...] Rather than seeing it, I see according to it and with it. (Merleau-Ponty 1993, p.126)

Here we return to the concerns laid out in the opening gambit of this thesis; that what is desired is to use cameras to unlock or explore new and different ways of looking at, and being with, sculpture. The official Tate video is the type of film which takes the medium’s transparency as a given, using its ability to reproduce the visible as a means by which to illustrate a conceptual and historical argument. The films made by the participants were an expression of a certain type of bodily experience, of tackling the spatial and physical qualities of the work at close hand. One thing that was particularly noticeable was the way in which participants often held the cameras at arms-length, unconcerned with the image on the camera screen. This was a type of filming connected as much with the hand and arm as with the eye.

Whilst this approach has not been one I have pursued in the studio practice, it opens up an important aspect of the research linked with the body, and in particular the hands. Throughout my filming I have, in various ways handled, caressed, shoved, tipped and moved the sculptures I have made in front of the camera. This is partly to do with scale. The sculptures in the Tate - of which there were a number by Henry Moore - were large, allowing the camera to be moved around, under and through them. The sculptures I have made by contrast tend to be far smaller, almost camera-sized, fitted to the hand which moves them around on the screen. Equally the camera has largely remained fixed within the studio. This is partly a practicality. When working alone and needing both to operate the camera and handle objects in front of it, it has been necessary for the camera to remain fixed. This has allowed a shift in the undertaking, where it might be seen that it is the objects which perform, becoming an active element within the situation. Unable to look through the viewfinder or see the display screen prompts a more physical mode of working, thinking less in terms of composition and image, and addressing instead, the sculptures’ objecthood and physical form.

There are also several reasons why filming pre-existing sculptures has not been the focus of the research. Firstly, there are the practicalities of filming this type of sculpture, made by other artists and owned by collectors or galleries who have vested interests in the control of the works’ reproduction. It would have been nearly impossible to have loaned sculptures, and even reproducing images of them would have been fraught with copywrite issues. It was also important for my own artistic practice that the sculptures pictured in my films would be things I had made, rather than those of other people, as this would have prompted too many questions relating to authorship, which would have distracted from the focus of the research. Finally, a freedom is allowed by my making the objects myself. I need not be overly precious or deferential. As the objects are intended for filming and not for conventional gallery display, I have been able to be more physically adventurous, even at the risk of damaging objects in the process of filming.

As with those made on full zoom, many of my films including 9 Objects (2016) and Some of my sculptures move from right to left (2016), could be seen to offer the viewer tactile experiences. By displaying the sculptures tactility through physical handling or intensifying surface texture with stark lighting, these films explore the physicality of the objects at the same time as rendering them practically untouchable: unlike in the gallery where there is usually the opportunity to touch even when it is forbidden. Something similar is at work in the hand coloured 16mm footage which appears in many iterations of the research’s film material including split screen presentations and gifs (this 16mm footage shows me handling objects, or sliding them back and forth in front of the camera coverd with the constant flurry of coloured marks and lines. It should be easy to identify). This footage was created as part of the practical research that led to the film 9 Objects (2016) and, as described in detail in the Aphorisms text, was used as part of a workshop at Tate Modern, where I projected the negative film and then unrolled the whole one hundred foot reel of celluloid across the room inviting participants to hand colour the image in any way they chose13. Here the materiality and tactility of the film itself becomes a part of the viewer/participants experience of the image and of the filmed sculptures, as they are able to interact with the thousands of tiny images that make up the film. When re-projected the materiality of both film and objects are entwined within the viewer’s experience.

Most importantly this process of making sculpture in order to film has created a rich and dynamic relationship between the processes of construction and filming, which could never have been the case had I directed the camera solely towards pre-existing works. Had this been the case the pitch of the research would have been subtly but fundamentally changed, as the process of filming would have become the main force of my active engagement with sculpture. Instead what has emerged is a far more complex relationship between the various parts of the making process. It has also put consideration of these specific objects firmly in the spotlight and prompted in-depth analysis, both practical and theoretical, into what exactly it is that they are.

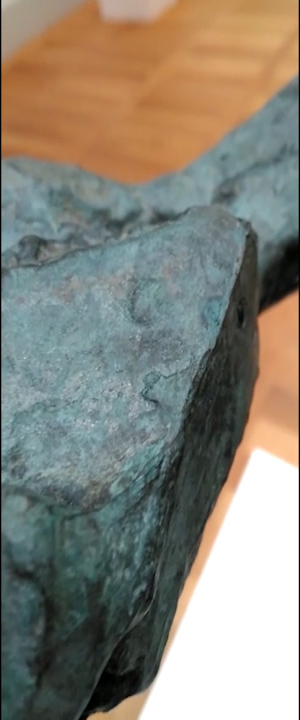

Stills from videos made by participants at 'Please Do Not Touch' workshop Tate Britain, 2016

Cameras have also been used in workshops to enable different ways of looking and of acting towards sculptures. One such workshop at Tate Britain entitled ‘Please do not touch’ (I was invited to run this workshop as part of the Tate London Schools and Teachers programme in May 2016. Referred to as a SEND Study Day, the workshop was for teachers and other arts professionals and asked them to consider ways in which young people with SEND might best use and inhabit the gallery and access the collection, through a series of practical activities) was particularly revealing. Participants were given cameras and asked to film sculptures in the collection on full zoom, trying to find ways in which the camera could offer different perspectives and ways of interacting with their physical, spatial and tactile qualities. This was predicated on two main ideas, firstly the propensity for people in galleries to step back when taking pictures, in order to get the whole thing in. A mode of viewing which emphasises pictorial composition. Secondly was the Tate’s priority for diverse groups to be able to use the galleries as they saw fit, working against traditional expectations of quiet contemplation. We were particularly interested in how young people with learning difficulties could access the collection. The irony was that touching the work was forbidden, yet to my mind, this would in many cases have been the most worthwhile and meaningful way for many of the young people I work with to access the work. Sculpture is after all tactile, spatial and massive (possessing of mass rather than being huge), and I felt should be physically experienced.

The idea to film sculptures using cameras on full zoom came initially from a reading of Alva Noë’s concept of human perception as an interconnected system of sensory experience (Noë 2004) – as opposed to what might be seen as the traditional privileging of sight as the dominant sense. Citing experiments where blind participants are able to respond to visual data received through tactile sensation, Noë shows that visual perception does not reach us purely through our eyes. In one such experiment fMRI brain imaging is used to show that tactile data is being processed within parts of the brain normally accosted with visual perception. Using technology that translates visual data from a camera into tactile sensations reproduced on the tongue, the subject (in this case one who is blind) is able to interpret visual sensations and, remarkably, recoil when a ball is thrown at the camera.

When looking closely at something, it is common to run one’s fingers over its surface in order to better make out fine detail through tactile exploration....What Finnish designer and master craftsman Tapio Wirkkala described as ‘“eyes at the fingertips”, referring to the subtlety and precision of the tactile sense of the hand.’ (cited in Pallasmaa 2009, p.54) This, I suggested to the participants, was something that might also be achieved through magnification. The question was, if we use zoom to focus in on fine surface detail, will this offer us impressions, ordinarily accessed through touch, which are forbidden in the context of the gallery?

Here, in something of a reversal of much of the studio work I had undertaken, in which the camera had encouraged the touching and handling of objects, participants created videos which attempted to gain this up-close sense of tactility through extreme close-up.

Before we began we had watched several short videos on the Tate Britain website in which works of art in the collection are discussed and filmed in a detached, measured and reflective way. (These films are available on the Tate website https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-britain/display/walk-through- british-art/1930 (Accessed: 5 September 2019)) The films made by the participants by contrast were frantic and full of movement as they used the camera to roam over the surfaces of sculptures, moving in and around, viewing them from angles which would be impossible or unlikely to be experienced by the standard gallery viewer. Unlike the videos on the Tate website, where sculptures were pictured as a whole, before certain elements were picked out and focused in on, (a structure of long view followed by close up which is typical of the way art objects are pictured in television documentaries- techniques pioneered in such programmes as John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) and Kenneth Clarke’s Civilisations (1969).), the videos created in the workshop had few if any wide shots. This meant that the impressions of texture and formal detail were not integrated clearly into the whole work as compositional elements, but were experienced as running into one another, giving these aspects an altered significance, one based in embodied experience rather than intellectual contemplation. Merleau-Ponty describes a similar sensation when gazing at the Lascaux cave paintings which follow the lines and contours of the rocky surface of the cave. ‘I would be hard pressed to say where the painting is that I am looking at. For I do not look at it as one looks at a thing, fixing it in its place. My gaze wanders within it [...] Rather than seeing it, I see according to it and with it. (Merleau-Ponty 1993, p.126)

Here we return to the concerns laid out in the opening gambit of this thesis; that what is desired is to use cameras to unlock or explore new and different ways of looking at, and being with, sculpture. The official Tate video is the type of film which takes the medium’s transparency as a given, using its ability to reproduce the visible as a means by which to illustrate a conceptual and historical argument. The films made by the participants were an expression of a certain type of bodily experience, of tackling the spatial and physical qualities of the work at close hand. One thing that was particularly noticeable was the way in which participants often held the cameras at arms-length, unconcerned with the image on the camera screen. This was a type of filming connected as much with the hand and arm as with the eye.

Whilst this approach has not been one I have pursued in the studio practice, it opens up an important aspect of the research linked with the body, and in particular the hands. Throughout my filming I have, in various ways handled, caressed, shoved, tipped and moved the sculptures I have made in front of the camera. This is partly to do with scale. The sculptures in the Tate - of which there were a number by Henry Moore - were large, allowing the camera to be moved around, under and through them. The sculptures I have made by contrast tend to be far smaller, almost camera-sized, fitted to the hand which moves them around on the screen. Equally the camera has largely remained fixed within the studio. This is partly a practicality. When working alone and needing both to operate the camera and handle objects in front of it, it has been necessary for the camera to remain fixed. This has allowed a shift in the undertaking, where it might be seen that it is the objects which perform, becoming an active element within the situation. Unable to look through the viewfinder or see the display screen prompts a more physical mode of working, thinking less in terms of composition and image, and addressing instead, the sculptures’ objecthood and physical form.

There are also several reasons why filming pre-existing sculptures has not been the focus of the research. Firstly, there are the practicalities of filming this type of sculpture, made by other artists and owned by collectors or galleries who have vested interests in the control of the works’ reproduction. It would have been nearly impossible to have loaned sculptures, and even reproducing images of them would have been fraught with copywrite issues. It was also important for my own artistic practice that the sculptures pictured in my films would be things I had made, rather than those of other people, as this would have prompted too many questions relating to authorship, which would have distracted from the focus of the research. Finally, a freedom is allowed by my making the objects myself. I need not be overly precious or deferential. As the objects are intended for filming and not for conventional gallery display, I have been able to be more physically adventurous, even at the risk of damaging objects in the process of filming.

As with those made on full zoom, many of my films including 9 Objects (2016) and Some of my sculptures move from right to left (2016), could be seen to offer the viewer tactile experiences. By displaying the sculptures tactility through physical handling or intensifying surface texture with stark lighting, these films explore the physicality of the objects at the same time as rendering them practically untouchable: unlike in the gallery where there is usually the opportunity to touch even when it is forbidden. Something similar is at work in the hand coloured 16mm footage which appears in many iterations of the research’s film material including split screen presentations and gifs (this 16mm footage shows me handling objects, or sliding them back and forth in front of the camera coverd with the constant flurry of coloured marks and lines. It should be easy to identify). This footage was created as part of the practical research that led to the film 9 Objects (2016) and, as described in detail in the Aphorisms text, was used as part of a workshop at Tate Modern, where I projected the negative film and then unrolled the whole one hundred foot reel of celluloid across the room inviting participants to hand colour the image in any way they chose13. Here the materiality and tactility of the film itself becomes a part of the viewer/participants experience of the image and of the filmed sculptures, as they are able to interact with the thousands of tiny images that make up the film. When re-projected the materiality of both film and objects are entwined within the viewer’s experience.

Most importantly this process of making sculpture in order to film has created a rich and dynamic relationship between the processes of construction and filming, which could never have been the case had I directed the camera solely towards pre-existing works. Had this been the case the pitch of the research would have been subtly but fundamentally changed, as the process of filming would have become the main force of my active engagement with sculpture. Instead what has emerged is a far more complex relationship between the various parts of the making process. It has also put consideration of these specific objects firmly in the spotlight and prompted in-depth analysis, both practical and theoretical, into what exactly it is that they are.